The Bear’s Last Roar: How Putin’s Incompetence is Fueling a Revolt Against the Kremlin

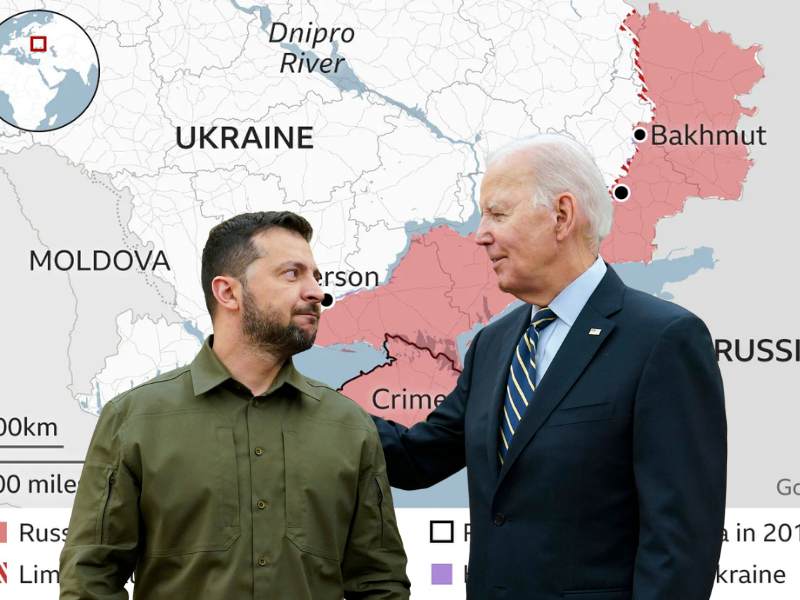

For over two years, Vladimir Putin‘s “special military operation” in Ukraine has devolved from a swift and decisive blitzkrieg into a humiliating quagmire. What was supposed to be a rapid subjugation of Ukraine has dragged on, with Putin failing at every turn. Now, it’s not just the NATO-backed Ukrainian forces he’s struggling against – his own people are refusing to fight his losing wars.

Let us take a deep dive into how Putin’s gross mismanagement and the Kremlin’s callous disregard for its conscripts have driven Russia’s soldiers and citizens to the brink of revolt.

The Tide Turns in Kursk

The seminal moment that may have turned the tide of this entire conflict was Ukraine’s unexpected invasion of Russia’s Kursk region. For 30 months, Russia had been the aggressor, pushing deeper into Ukrainian territory. But in a shocking reversal, Ukraine crossed the border and seized control of dozens of towns and villages in Kursk.

This was no mere skirmish. The Ukrainian forces, bolstered by Western artillery and equipment, overwhelmed the poorly trained and equipped Russian conscripts stationed in the region. Distressingly, over 80% of the Russian troops captured in Kursk were found to be conscripts – young men forced into service rather than seasoned, contracted soldiers.

The conscripts, given minimal training and thrust into the heat of battle, proved no match for the determined Ukrainians. Video footage emerged of Russian soldiers simply surrendering en masse, with the Ukrainian military capturing nearly 600 prisoners of war from Kursk alone.

This debacle laid bare the fatal flaws in Russia’s military recruitment and deployment strategy. Unlike the United States, which has centralized basic training for all recruits, the Russian army’s training is highly decentralized. Each unit is responsible for conducting its own instruction, leading to vast disparities in the quality and duration of soldier preparation.

Compounding this issue is the fact that Russian conscripts only serve for one year, far less than the extensive training regimes of Western militaries. These conscripts are often relegated to administrative or menial roles, with little time spent on combat simulation and live-fire exercises. When suddenly thrust into the crucible of battle, they crumbled against the battle-hardened Ukrainian forces.

The Kursk invasion also shattered the Kremlin’s carefully crafted narrative. For months, state media had assured the Russian public that the “special military operation” was going according to plan, that Ukraine’s forces were being swiftly defeated. But the collapse in Kursk laid bare the truth – Russia’s military was woefully unprepared and outmatched.

The Specter of Afghanistan and Chechnya

This is not the first time Russia has struggled with the use of conscripts in warfare. The Soviet Union’s disastrous involvement in the Afghan conflict, known as the “Soviet Vietnam,” was a prime example of the perils of relying on ill-trained and unmotivated conscripts.

By the time the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, it had lost an estimated 15,000 soldiers, many of them conscripts. This contributed to a growing public discontent with the Soviet regime, as the sacrifice of these young men was seen as senseless and fruitless.

The First Chechen War in the mid-1990s saw a similarly dire outcome for Russian conscripts. Sent to fight in a bloody civil war, an estimated 10,000 Russian soldiers perished, with hundreds of thousands of civilians displaced. The public outcry was deafening, leading Russia to pass a law prohibiting the deployment of conscripts abroad.

Yet, the draft remained, and draft-dodging became a national pastime, with young men going to great lengths to avoid military service. Now, with Ukraine’s invasion of Kursk, the specter of conscripts being thrust into the meat grinder once again looms large.

The Kremlin’s Crumbling Social Contract

The Kursk debacle has also driven a wedge between Putin and a crucial power base: the Russian oligarchs. These wealthy industrialists, many of whom amassed fortunes in the energy sector, have long been integral to the Kremlin’s power structure.

But the war in Ukraine has upended this delicate balance. Overnight, Russia lost some of its largest trading partners in the West, forcing the Kremlin to hastily forge new deals with China and India – arrangements far less lucrative than the previous European contracts.

Oligarchs like Oleg Tinkov have begun to openly criticize the war, renouncing their Russian citizenship. Others, such as Mikhail Fridman, have resorted to more muted grumblings, aware that Putin still retains a firm grip on their operations.

Faced with crippling Western sanctions and the loss of their economic lifelines, these oligarchs have become liabilities rather than assets for the Kremlin. Putin has seized the opportunity to further consolidate power, launching lawsuits to nationalize companies owned by the country’s wealthiest figures.

The social contract that has underpinned Putin’s rule is crumbling. The once-reliable pillars of the regime – the military, the oligarchs, and the docile urban populace – are all showing cracks. With conscripts surrendering in droves and the oligarchs voicing their discontent, the foundations of Putin’s power are shaking.

The Path Forward

As Ukraine continues to press its advantage, Putin faces a critical crossroads. He can double down on his conscription efforts, further straining the loyalty of the Russian people. Or he can concede defeat, a humiliation that may well jeopardize his grip on power.

Either way, the future appears bleak for the Russian president. The Kursk invasion has shattered the carefully crafted illusion of Russian military might, exposing the Kremlin’s callous disregard for its conscripted soldiers. The oligarchs, once Putin’s staunchest allies, are now eyeing the exits, and the public’s trust in the regime is eroding.

The bear’s roar is growing weaker, and the people are refusing to answer its call. Putin’s incompetence has lit the fuse of a powder keg, and the explosion may well consume him.

Table: Comparison of Russian and U.S. Military Training

| Russia | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Training Duration | 1-2 months | 10 weeks |

| Advanced Training Duration | 3-6 months | 22 weeks |

| Total Training Time | 4-8 months | 32 weeks |

FAQs

Q: What led to the Ukrainian invasion of Kursk?

A: For 30 months, Russia had been the aggressor, pushing deeper into Ukrainian territory. However, the Ukrainian forces, bolstered by Western artillery and equipment, unexpectedly crossed the border and seized control of dozens of towns and villages in the Kursk region.

Q: Why were Russian conscripts unable to defend Kursk?

A: The Russian conscripts stationed in Kursk were poorly trained and equipped, with over 80% of the captured troops being conscripts. Unlike professional, contracted soldiers, the conscripts received minimal training and were often relegated to administrative or menial roles, with little time spent on combat simulation. When thrust into battle, they crumbled against the battle-hardened Ukrainian forces.

Q: How have past conflicts involving Russian conscripts shaped the current situation?

A: The Soviet Union’s disastrous involvement in the Afghan conflict, known as the “Soviet Vietnam,” and the First Chechen War in the 1990s both saw significant losses of conscripted Russian soldiers. These conflicts contributed to growing public discontent with the regime and led to a law prohibiting the deployment of conscripts abroad, though the draft remained in place.

Q: How have the Russian oligarchs reacted to the war in Ukraine?

A: The war has upended the delicate balance between the Kremlin and the oligarchs, many of whom amassed fortunes in the energy sector. Faced with crippling Western sanctions and the loss of their economic lifelines, some oligarchs have begun to openly criticize the war, while others have resorted to more muted grumblings. Putin has seized the opportunity to further consolidate power, launching lawsuits to nationalize companies owned by the country’s wealthiest figures.

Post Comment